“History is a set of lies, agreed upon.” – Napoleon Bonaparte

Growing up in America, historical context, that is to say local historical context, is extremely limited. Dig down into the history of any well known city and eventually, inevitably, you’ll encounter the intangible before. Maybe, maybe a city will have records dating to the founding of a mission or fort from four or five hundred years ago. As a country, the 250ish years, including all the monolithic individuals, developments, and events, pale in comparison to the greater context.

Ask the indigenous peoples of North America for example, what two hundred years feels like and they might tell you to come back after a few thousand. One could argue that the American experience is largely devoid of context, of foundations beyond those crudely, hurriedly thrown up and made of sand. European history on the other hand, at least in terms of what was recorded, and is easily accessible, stands on limestone worn smooth by the passage of years, bearing imprints of the feet of those who lived through them

This long view is the central theme of Pentiment, a 2022 video game developed by Obsidian Entertainment. Listed as an “adventure” game, Pentiment, fully embodies this genre while also fully eclipsing it. Pentiment is one of the holy trinity of what I’ve come to recognize as the reinvigoration of narrative-focused gaming. What the Souls games did for combat, exploration, advancement, and accomplishment, games like Pentiment, Disco Elysium, and Citizen Sleeper are doing for narrative. These games are not only well written, they also push the interaction of player and story.

Pentiment takes place over a series of episodes spanning several decades in the Bavarian Alpine town of Tassing, and the nearby Kiersau Abbey. You assume the role of one Andreas Maler, aspiring artist who in 1518 is apprenticed as an illuminator of manuscripts at the aforementioned abbey.

Character creation deals less with the what and more with the why. Through various interactions, you are invited to collaboratively tell Andreas’ story. Maybe he studied a bit of medicine while he was at university. Maybe instead of studying, he spent his time carousing. Whatever you choose informs everything going forward. These are the earliest foundations you are invited to participate in. But this town, new though it is to us and seen for the first time through Andreas’ eyes, has a long history that runs, both figuratively and literally as we’ll find out, very deep.

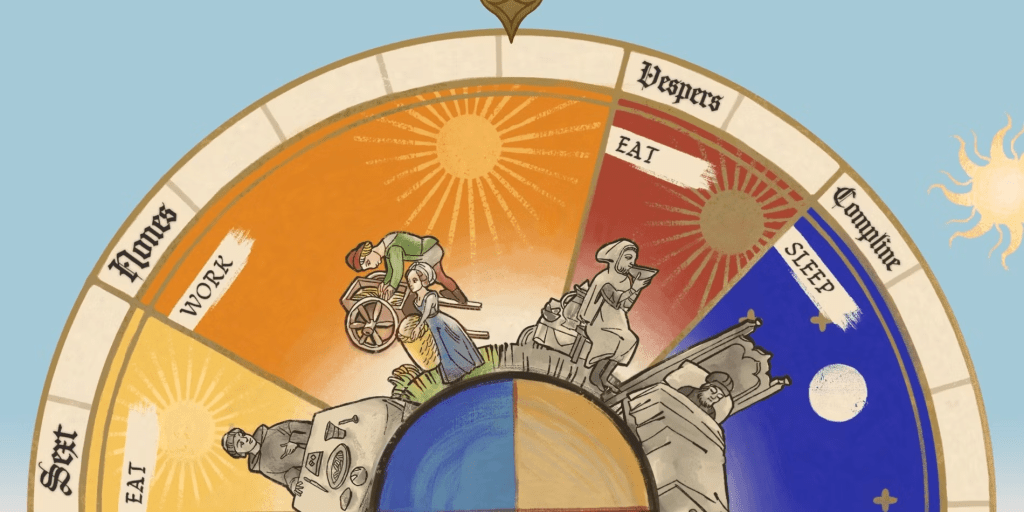

And the story begins! Your days are broken up into different segments informed by the perpetual turning of a beautifully illustrated wheel representing the different times of day as the people of that era would have recognized them. Morning, noon, and night? Nah. Here you’re looking at Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers, and Compline. Fun stuff. There are also subtle changes that take place regarding the clock mechanic that reflect the changing state of things in the world of that time. Without spoiling anything, it’s awesome to see level of attention to detail and historical accuracy.

Splitting your time between the town and the abbey, you very quickly get a sense of some inequality and tension. You are free to take whatever stance you prefer: Andreas can be a staunch proponent of the church who won’t tolerate any dissention, (including the Theses of Martin Luther, perhaps the hottest button topic to be found in a place like Tassing at a time like 1518), or he can be more progressive, recognizing the plight of the peasants and the injustices enacted and empowered by the church.

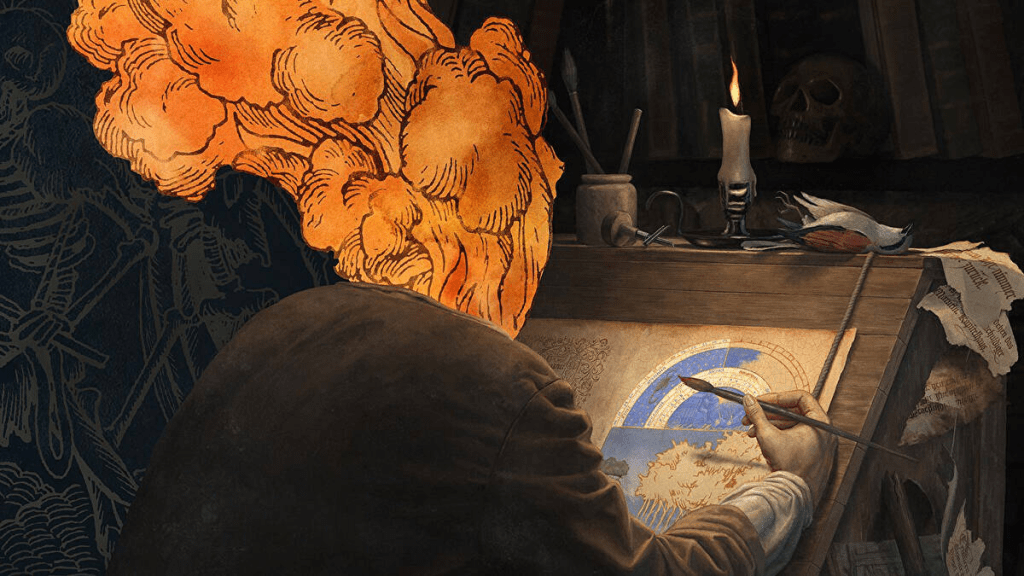

Andreas is currently hard at work in the abbey’s scriptorium, toiling away on what he, and the monks he’s working beside, recognize will be his masterpiece: an illuminated manuscript page. Interestingly enough, I happened to watch The Name of the Rose during my playthrough of Pentiment, and it served as a wonderful companion piece. While not a perfect film, you can see many of the same environments and settings from the game in a different representation.

The first few days pass uneventfully from Andreas’ perspective: what could be more fulfilling for a budding artist than to have time designated solely for one’s passion (art) in a beautiful pastoral mountain town? But the seeds of what is to come were sewn long ago and are evidenced in the interactions Andreas has with the townsfolk. In particular an early and recurring theme is the reality of life for women: it was pretty awful. Having little legal recourse, often times the only path to power for women was through the church, and this comes up time and again.

Speaking of the townsfolk, Pentiment assumes the mantle of every Creative Writing 100 instructor: show, don’t tell. Over the course of years you are introduced to families and are able to follow their progressions. Children grow older and marry, having children of their own. The game clues you into this by the character designs: colors are used to brilliant effect here. Family members are dressed similarly, can be recognized by the color of their hair, or sometimes by the reflection of their profession upon their appearance. Yet even these families Andreas interacts with are but a drop in the bucket of the historical pool flowing beneath Tassing.

Traveling back and forth between the abbey and town reveals the larger world to you: an ancient salt mine occupies one corner, a giant column another, a partially collapsed aqueduct stretches across the horizon as you transit from one screen to another. Andreas finds out almost immediately that these are Roman ruins, and the foundations of the abbey are made of the bones of a Roman fort from a time before. The people of Tassing bring this up at various points: are we Romans? Are we Bavarians? Are we something else, heathens perhaps? What is the truth of Tassing? Of Kiersau?

Soon there is murder most foul! Andreas decides to leverage all his skills to help prove the innocence of a friendly monk who stands accused. Here is where the time mechanic really sings: you don’t have time to do everything in one playthrough. You must make hard choices, frequently.

Andreas has a map that reflects points of interest, keeps track of quests and objectives, and also keeps tabs on all the characters you’ve encountered with brief descriptions and details of each. Something I loved was that not everything important is highlighted on the map. The game does help you, but also rewards exploration.

Skills chosen earlier come heavily into play as you investigate. Can Andreas speak a little Latin? He’ll put that to good use deciphering clues. That medicine skill he dabbled in? Yup – it will help you conduct an autopsy and see things that would otherwise go undiscovered. The sheer amount of permutations possible are staggering – I can’t wait to see how Andreas conducts himself with a different set of skills on my next playthrough.

Eventually things come to a head and you are forced to make a decision, a decision that will result in further loss of life no matter what you do or how well you investigated. But did you choose correctly? What ripples will your decision bring in your own life, and into those of the people of Tassing? Did you choose correctly? Was there a correct choice? Whatever you choose, you’ve got to live with it.

In between segments, you are occasionally taken to what is revealed to be Andreas’ mindspace. He encounters various characters representing aspects of himself that he can interact with. They offer council, and periodically warnings. These interstitial moments are some of the best in the game, and the changes illustrated within Andreas’ mind over time are fantastic. Themes of mental illness are touched on with increasing fervor as Andreas grows older and experiences more and more. Here again we are invited to collaborate on Andreas’ story. What happened with his marriage? How does he feel about it? Is he happy? Was he ever happy?

Speaking of Andreas’ mindspace, occasionally over the course of discussions a thought bubble will appear. These prompts allow you to step through lines of thinking inside Andreas’ mind, and can be very helpful in deciding how to respond in certain situations. Another mechanic directly linked to discussions is that of persuasion points. Things you say, and choices you make are sometimes accompanied by bold text informing you that they will be remembered. These culminate in persuasion points: unannounced moments where, depending on the conversation path you’ve woven, you may or may not be able to convince someone of something. Here again the game helps you out but doesn’t do everything. There are choices to be made, some of them with enormous consequences, that go by unheralded by bold text.

Time passes and we rejoin Andreas seven years later. The choices we made in the past are on full display in the present. The game continues in a similar fashion, leading to another impossible choice, another passage of time, and finally the third and final segment where the questions of foundation come full circle. How will the story of Tassing be told? What will be included and left out?

Pentiment is a gorgeous game from start to finish. Character designs are wonderfully expressive and individual. The designers and artists managed to make the poor huddled masses toiling in the darkness of the middle ages recognizable as individuals, each with pasts, presents, and hopes for the future. Likewise, the monks of the abbey, clad in drab robes though they may be, are elevated to individuality by their quirks, stature, and minute details that will stick you long after you’ve reached the credits.

Your choices matter more than the foundations you stand on when you make them: this is the ultimate message of the game, and one that I found refreshing and invigorating. You are here, the starting point, and context, while important, exists only to serve as a point to launch from.