We’re living in an exciting (and worrying) era for survival horror. Dormant or ignored franchises are being resurrected and brought back to relevance, mostly with success. Resident Evil is (mostly) good again! Dead Space got a remake! Alan Wake 2 finally came out and didn’t disappoint! And after a handful of mediocre Silent Hill sequels, Bloober Team, the development house behind the Layers of Fear games, Observer, The Medium, and more, gained worldwide attention for remaking one of the pillars of the survival horror pantheon: Silent Hill 2. While playing it mostly safe, that game dragged Silent Hill back into relevancy. Now the only thing we have to fear is Konami’s decision to adopt an annual release schedule. Even though the games in the Silent Chute (Townfall, and possibly a remake of the original) look and sound promising, this bit of news is extremely concerning. Quantity over quality will only lead us back into the drought from whence we only recently emerged, like longnecks searching for tree stars.

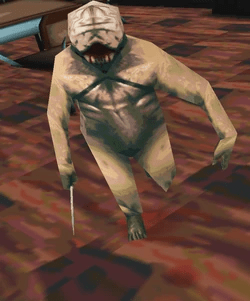

After leaving their mark on the survival horror world, Bloober Team turned their attention to the creation of a unique horror IP, a dangerous endeavor, regardless of previous successes. Cronos: The New Dawn is the result of those efforts. What feels like the love child of 12 Monkeys and Dead Space, the game overwhelmingly succeeds in what it sets out to do. Oppressive setting and environments? Check. Disgusting, squidgy enemies? Check. Mounds of roiling flesh for the player to navigate? Check. A nameless protagonist whose only identifying moniker is a number? Check.

But these things alone wouldn’t necessarily make a survival horror game in this, the year of our lord 2026, remarkable or memorable. It’s the attention to detail, the wonderful writing, and the performances that make Cronos stand out.

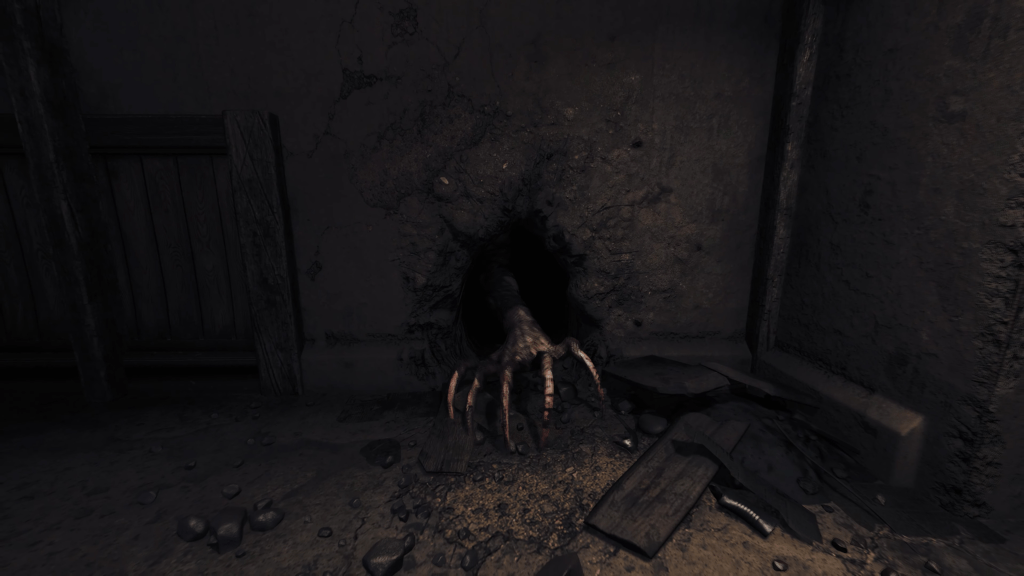

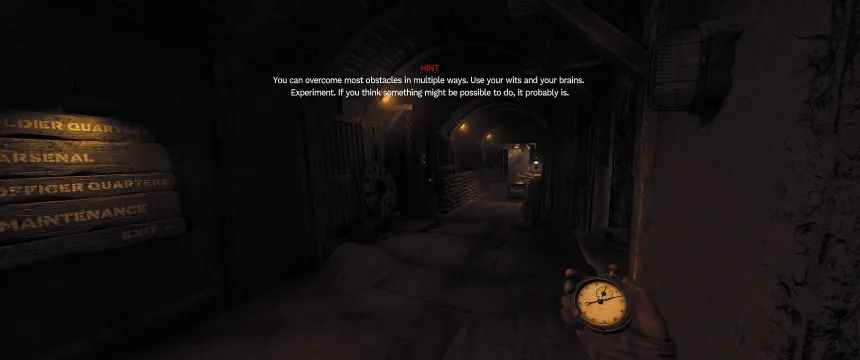

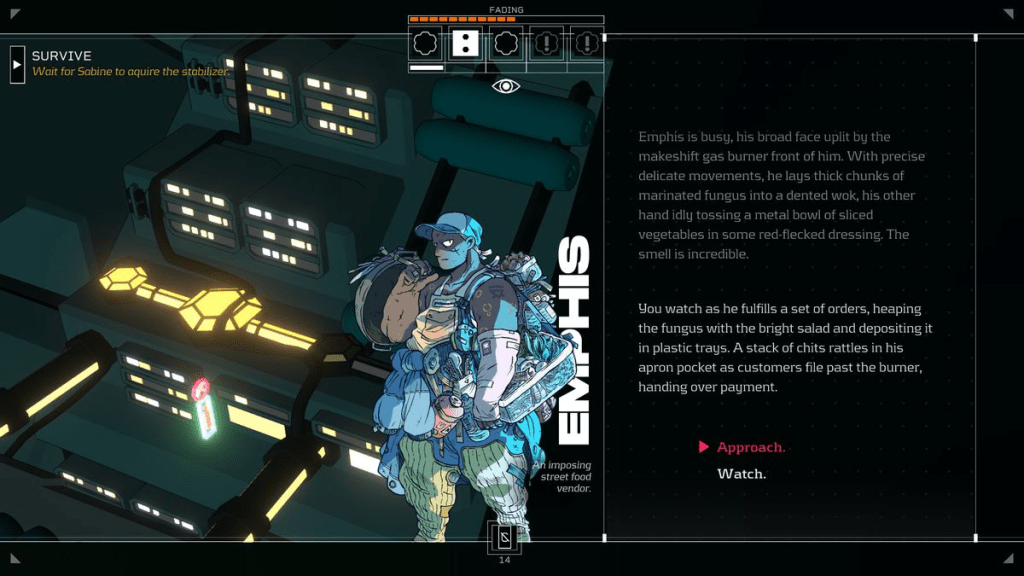

You take on the role of the Traveler, ND-3576, a lumbering hulk of a humanoid shape, who more closely resembles a diving bell than a human being. But somewhere in there lurks humanity of a type. Immediately you are tested, interrogated, and prompted to respond to stimulus without context. Your choices waver through the lips of what sounds like a waifish, middle-aged woman, who by the sound of her voice, is barely extant at all. Once all questions have been answered, you are armed, and unleashed upon whatever world awaits you beyond the massive sealed door. Immediately you get the sense of decay, of rust, of time’s heavy hand upon the landscape. Sand dunes have piled up around everything; what structures still stand have been beaten into submission by weather; yet it somehow feels familiar? Have you been here before? Are those footsteps in the dust?

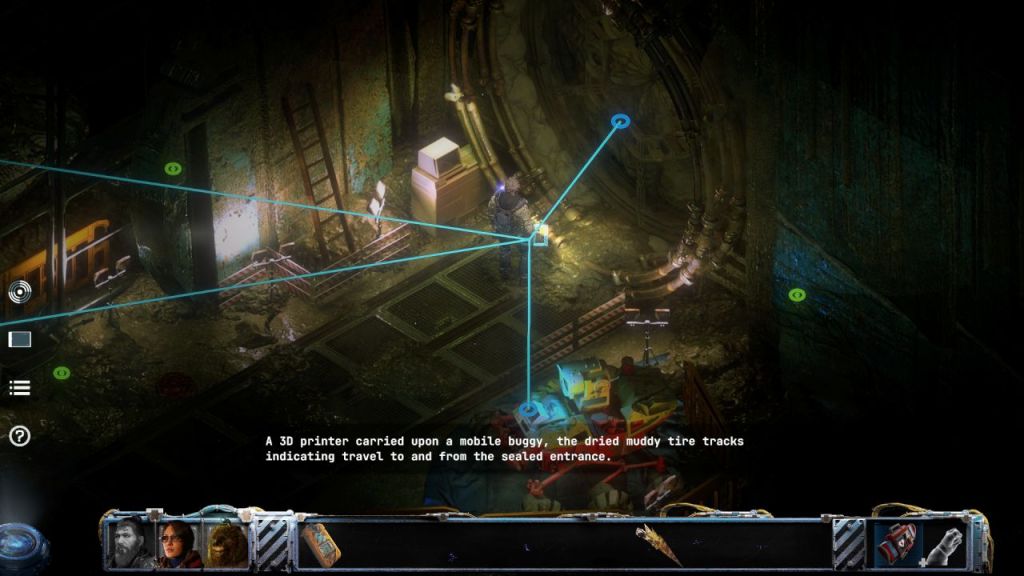

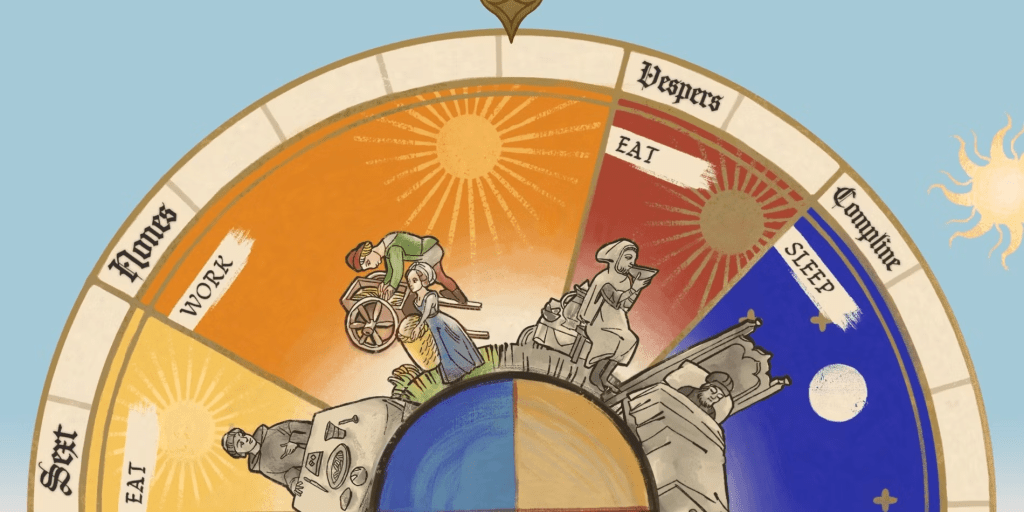

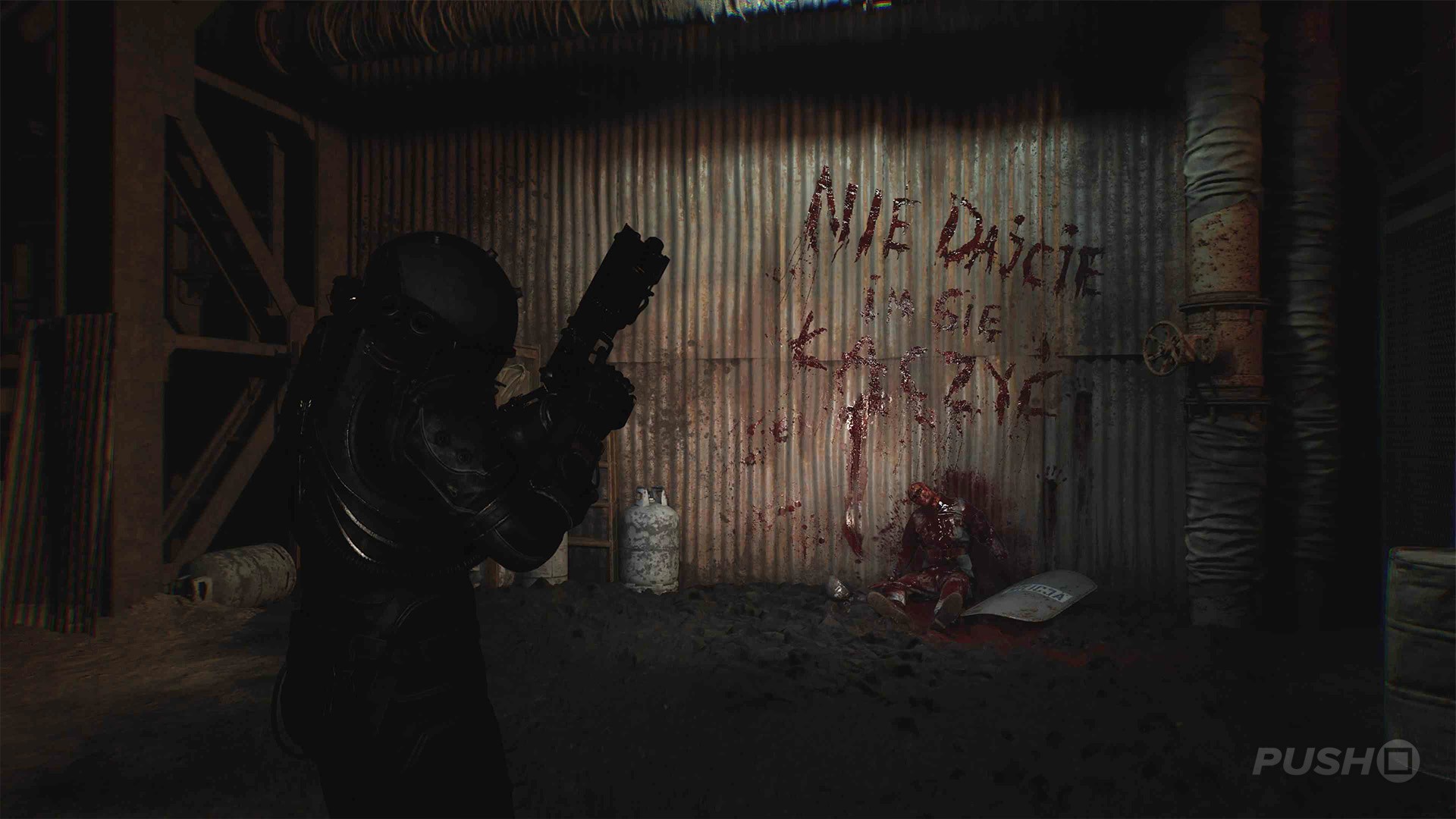

Conciseness. Identity. Persistence. Soon a pip-boyesque device on your arm begins to guide you upon the great quest. Your first mission: find and extract a man named Edward Wiśniewski. Here’s one of the first hints of the broader setting: you’re exploring a parallel Poland from the 1980s, complete with the technology and style you’d expect to find. An early gripe, but a minor one: The characters all have extremely Polish names, yet all speak (for the most part) in unbroken, unaccented English. Games got to game, I understand that, and knowing how people in general hate reading and subtitles, I get the decision, but…my immersion!

Here’s another mostly positive, tinged with negative: the environmental storytelling. One of the main ways the game achieves this is through messages graffitied across walls and governmental posters scattered around. These are not written in English. If you move your reticle over them, their translations will appear. Most of the time. I’d say about 65% of the time. What’s the deal with that? You introduced a storytelling mechanic that hooked me, and I floated along in blissful serenity. Until I found a poster that wasn’t translated! If you’re going to do something like this, it’s got to be all the way.

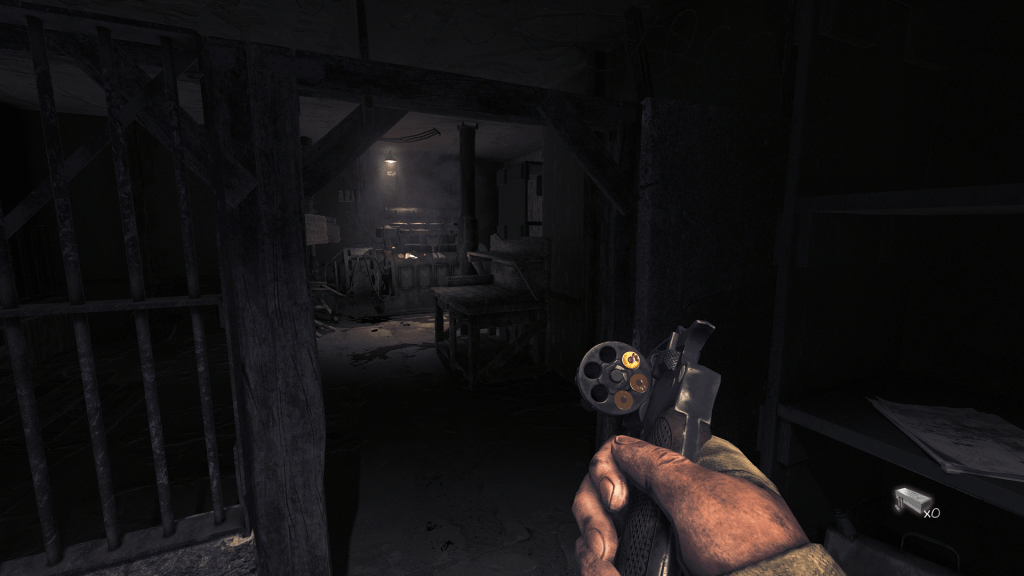

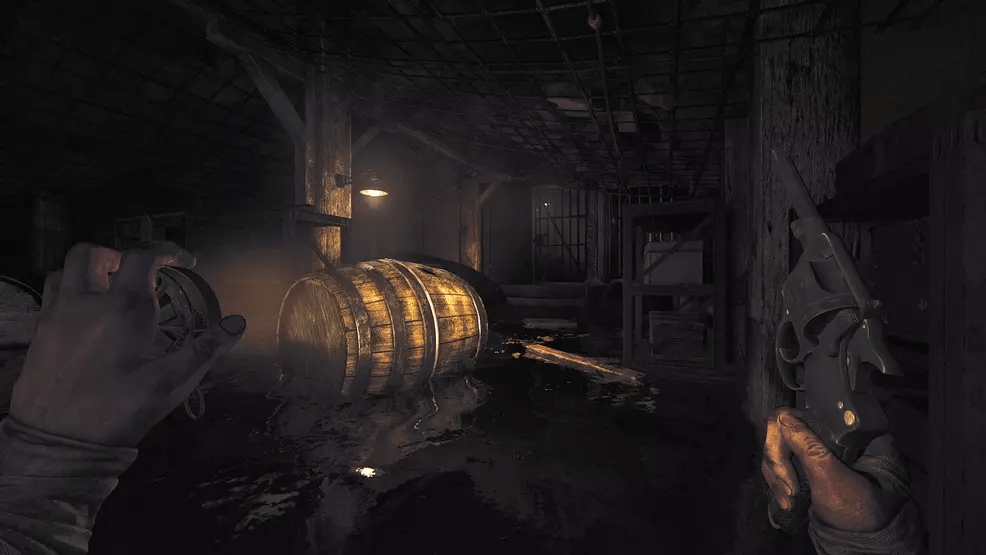

Gameplay is pretty standard survival horror affair, of the “enemies occasionally drop ammo” variety. Over the course of the game you get two versions of the old standard weapons: pistol, shotgun, and carbine, along with a big mamma jamma. An essential mechanic is charging up your shots. If you just squeeze of round after round, you won’t do enough damage to survive long. This leads to tense strategizing wherein you’ve got to decide when to begin the charge and when to unleash. And no matter how good it feels to land a shotgun splash blast into a group of enemies, it just won’t touch the agony of wasting said blast on a single enemy or missing entirely.

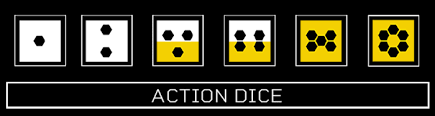

Upgrades are split between your “shell,” the bulky suit you call home, the few gadgets you obtain, and your weapons. Shell and gadget upgrades come in the form of cores while weapons require energy (money). Early on, the core upgrades you choose are essential, as you begin your journey with only 4 inventory slots! Weapon respeccing is available and quite forgiving in terms of cost. Soonish you are introduced to another recurring feature: chained gateways requiring bolt cutters to enter. Is it worth the inventory space? Let me answer that question with another question:

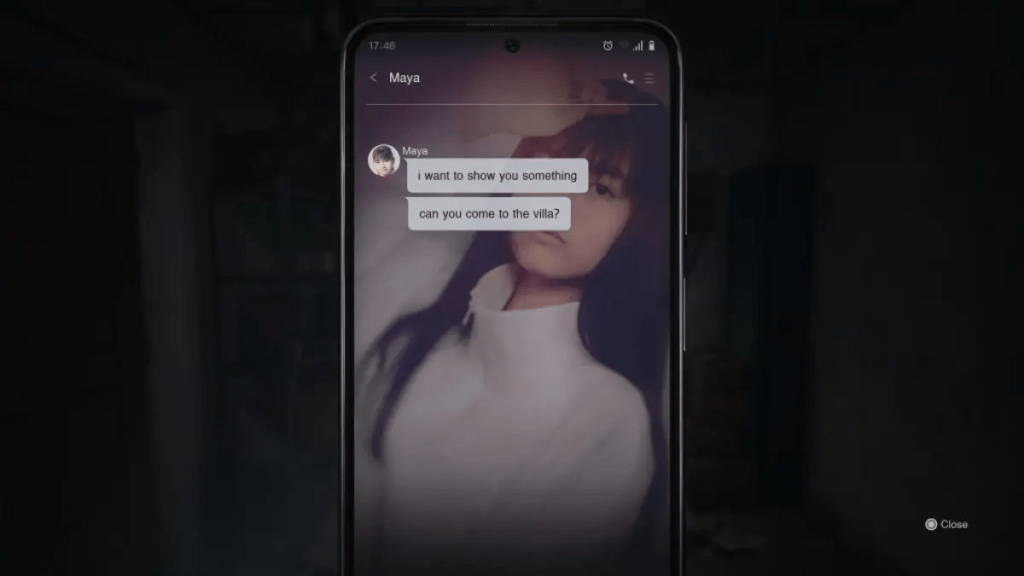

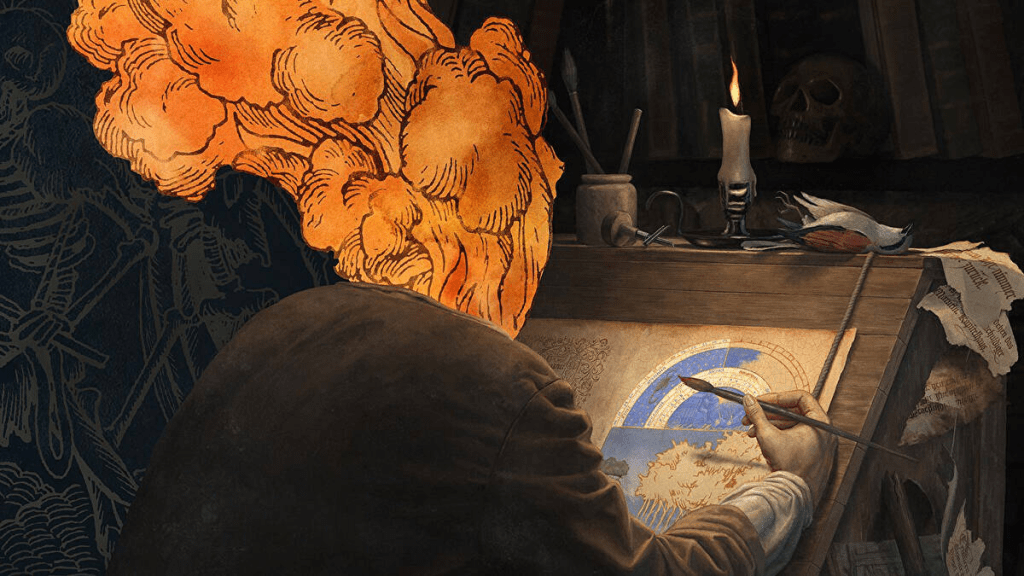

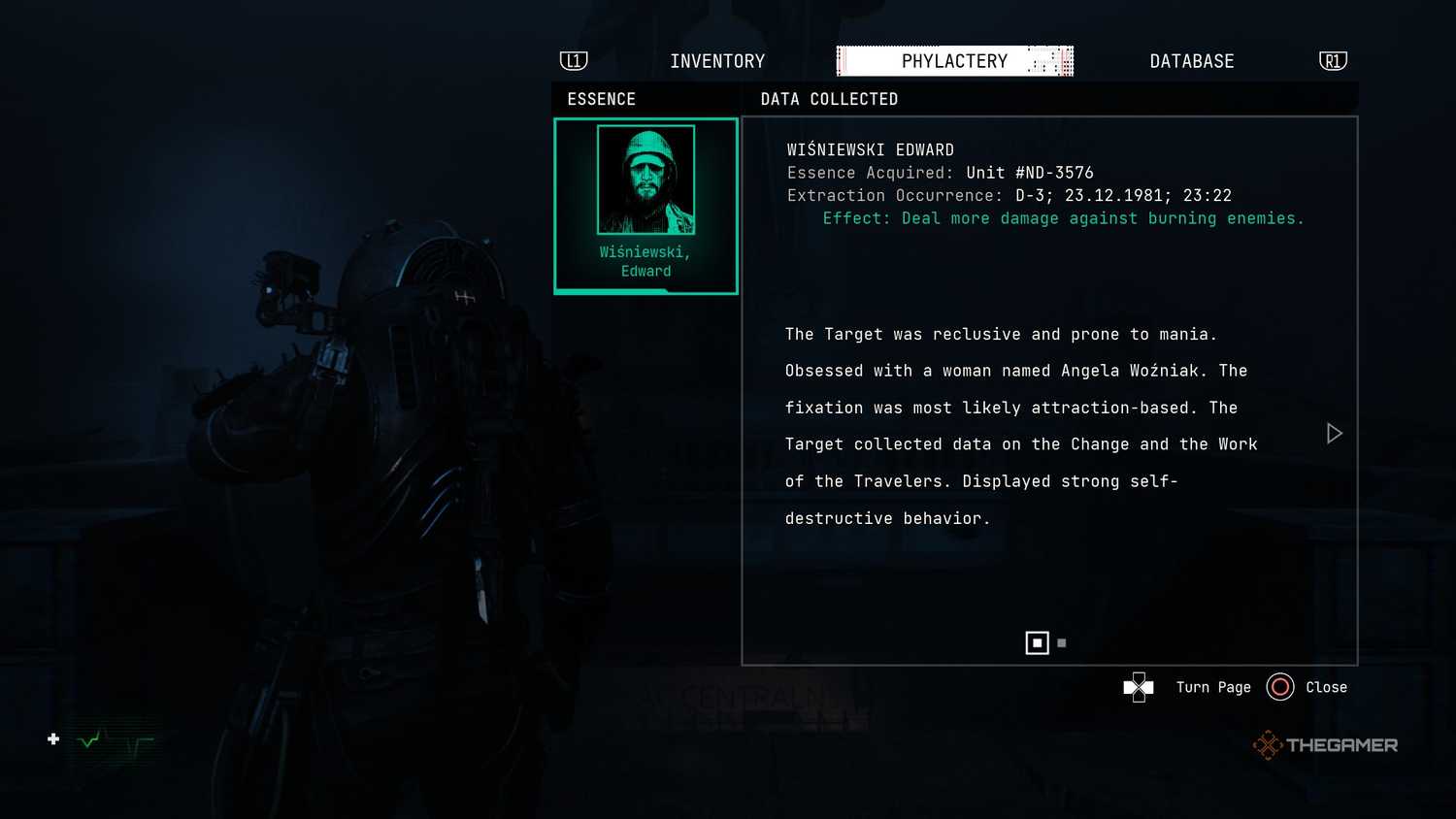

So what’s the story? Essentially you are a time traveler bouncing around, “extracting” individuals who may hold information relevant to understanding and/or rectifying whatever disaster unleashed the monstrous Orphans upon the world. Extracting in this sense meaning the horrifying process of removing a person’s consciousness with the intent of later uploading it to the Collective, the organization to which the Traveler (that’s you) belongs. Each essence grants a passive effect, which can have a significant impact upon your play style and success.

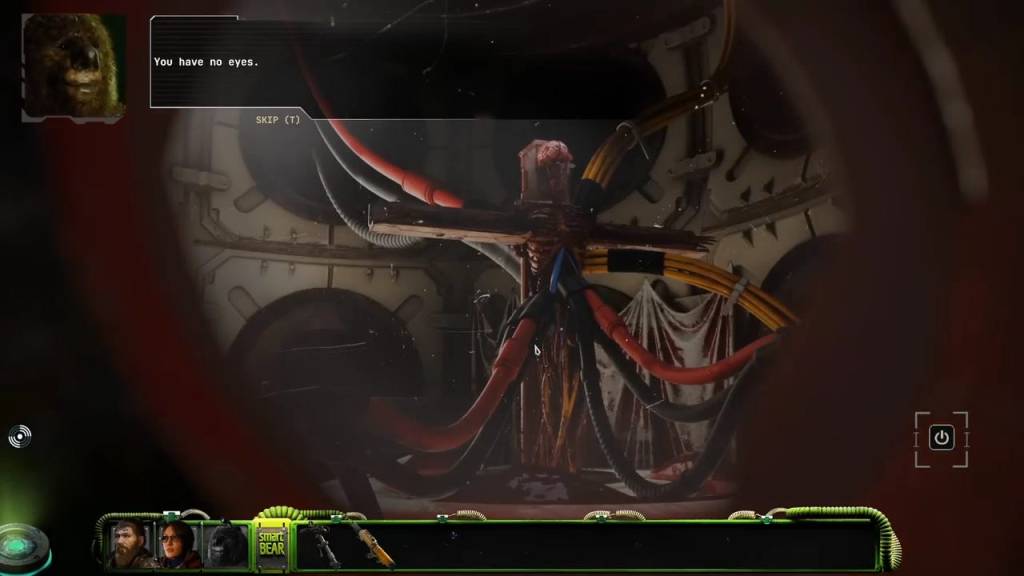

But of course there’s a wrinkle. Oh, there’s always a wrinkle. You can only hold 3 essences in your phylactery. What happens if you exceed this number, you ask? You’re given the choice of which you want to discard. And then you see the most horrifying progress bar in the history of computational tracking, accompanied by the final words, or frequently screams, of the subject that’s being deleted. Jesus. Christ. Another thing about these essences. As you move through the world, you will hear different ghost dialogue depending on who you have stored in your phylactery. Pretty cool.

Eventually you arrive at the terminal, or central hub, if you will. And here you meet the only other being similar to yourself: the Warden. As bashed and battered as you appear, the Warden looks worse off. He’s missing an arm and a leg and has acquired ersatz replacements.

The interactions between the Warden and the Traveler were fantastic, and really shine as some of the best sequences in the game. If you take the time to resolve all the optional dialogue (which I would not consider optional) you will be well rewarded. You’ll talk about those strange creatures you’re working around, humans, as well as another strange creature: the cat! Here’s another recurring mechanic: kitties lost in the wasteland that you can save and bring back to the safety of the Terminal. Periodically, you’ll hear the faintest mew, and with a bit of tenacious exploring, you’ll find the mewer. And a reward!

You’ll encounter a core cast of characters the Traveler seeks out, along with several others that you stumble upon. This core cast is who we follow throughout the course of the story. We learn about things before, during, and after the event, and how everything intersects with this group.

There’s a late game twist that struck me as so-so: if you’ve delved into games, movies, or stories of this type before, you probably will see it coming. That said, the various endings felt fulfilling. There’s one last ending available after completing new game plus that really ties things up.

Other minor gripes? Some cutscenes were skippable and others weren’t. I believe this is due to the fact that there are choices to be made in some of these. OK. But why can’t I skip it on my subsequent playthroughs? Or let me skip lines of dialogue instead of the entire scene?

Some people will hate the fact that you don’t control when the flashlight turns on or off. I can see both sides. It didn’t bother me as I get that they’re using it as a tension-building device. But after the fifth time the flashlight sputters out and dies, and you hear another lumbering monstrosity moving nearby, you just expect what’s coming next.

Other highlights? The music is great. Very Stranger Things. It just feels perfect for the setting and gameplay. I mentioned the voice acting earlier, but to me it is the best thing about the game. The Traveler and the Warden just sound so utterly exhausted. Depleted. Like they’re being made to endure these trials for the millionth time. Inevitably, Cronos will be compared to Dead Space, and rightly so as it is clearly a huge inspiration. I think the gameplay between the two is up for debate, but in terms of story and storytelling? I think Cronos eats Dead Space’s lunch.